Case Closed: What Carpenter v. United States means for your privacy

Happy Summer!

It was only time until we saw Internet privacy hit the highest court of the land: the Supreme Court. This past Friday, the Supreme Court made their final ruling on the “Carpenter v. United States” case, a case surrounding the privacy of cell-site location. As a citizen, it becomes important that we understand our rights granted and protected by the Constitution, in order to best exercise them. As we transition into this digital era, where data about our whereabouts, health status, networks, finances, and history are all stored online, it becomes even more crucial that we fully grasp how the Constitution protects our digital rights. The case of “Carpenter v. United States” has been a landmark case in defining this for our society. Today, we will dive into what this case was all about, both sides of the story, and what the final decision means for our future of privacy.

What did Carpenter and the Government do?

In December 2010, a series of armed robberies hit metro Detroit, Michigan, and Northern Ohio. The police ended up arresting some of the 4 men, with one of the men giving the police the phone number of petitioner Timothy Carpenter. With this number, law enforcement requested information from cell phone companies T-Mobile and MetroPCS under the Stored Communications Act of 1986, which says that data can be shared without a warrant, as long as the government provides “reasonable grounds” to believe the information is relevant and will help in the said case. To put this in perspective, “reasonable grounds” has a much lower threshold than the 51% “probable cause” needed to obtain a warrant. However, still, under this justification, 127 days of cell-site data (12,898 data points) on Mr. Carpenter was shared with law enforcement, placing him precisely in the vicinity of each of the robbery sites and becoming the basis on which he was convicted.

Source: Motherboard

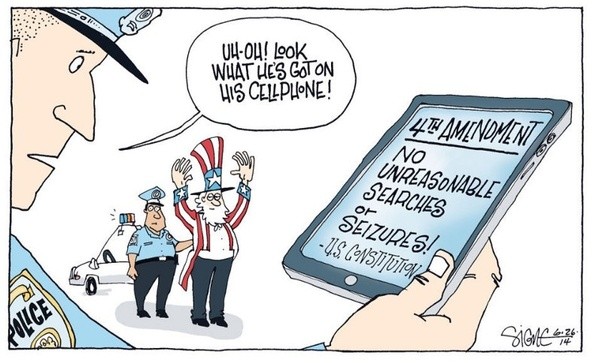

However, in obtaining the cell-site information, prosecutors did not obtain a warrant, which would have required them to already have “probable cause” that the records were evidence of the crime. Because of this, Mr. Carpenter returned claiming a Fourth Amendment violation, saying that he possesses a “reasonable expectation of privacy,” and that even though prosecutors did find evidence after the fact, they needed a warrant to obtain it in the first place.

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. – Amendment IV, United States Constitution

The highly debated case was taken to the Supreme Court.

Recapping the Arguments

Prosecution: Under the Third Party Doctrine, by voluntarily using his device and disclosing information to any third party, which in this case was his phone company, his information was no longer private and no longer protected under the Fourth Amendment.

Petitioner: Mr. Carpenter was represented by the American Civil Liberties Union’s (ACLU) Nathan Wessler, who emphasized that our digital devices now share the most intimate details of our lives, telling about our relationships, our everyday routines, our work/life balance, and even our sexuality. He described our phones as a “time machine that can trace your every move.” With this, he also brought up that everyone emits this data off of them about their private and sensitive information. Thus, he said, the government has now become responsible to have that 51% probable cause in order to conduct a “search and seizure” on our data. He focused on future implications of allowing data to be

Source: American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)

The Court’s Decision

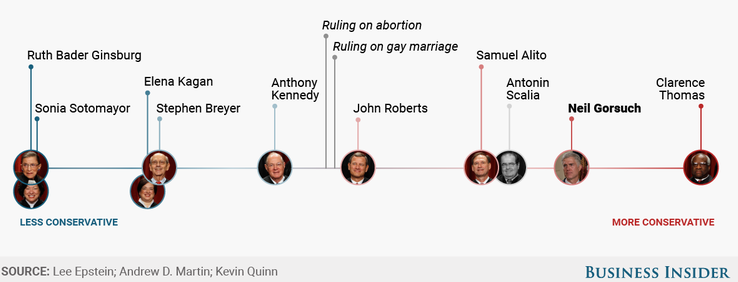

The decision was a 5-4 decision in an opinion by Chief Justice Roberts on June 22, 2018, in favor of the petitioner. Justice Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan joined Justice Roberts in this opinions. On the other hand, Justice Kennedy filed a dissenting opinion alongside Justices Thomas, Justice Alito, and Justice Gorsuch.

Chief Justice Roberts, although aligning himself with the beliefs of the court’s liberal wing, a rare move from him in close cases like these, has continually displayed focus on protecting our constitution’s granted privacy rights as technology advances.

Supreme Court Justices Ranked by Ideology Source: Business Insider

Timeline of Supreme Court on Digital Privacy

Our higher courts have proven to decide each case of 4th Amendment and technology circumstantially, rather that on structured reasonings. This has been proven by the cases Smith v. Maryland in 1979, United States v. Jones in 2012, and Riley v. California in 2014. On one hand, in Smith v. Maryland in 1979, the Court sided with the state, ruling that it was justifiable that the phone company installed a device to record the phone numbers a suspect called from his home phone without a warrant.

However, on the other hand, in both the cases of United States vs. Jones and in Riley v. California, which were more recent cases, the court ruled in favor of privacy, saying that a “warrantless” cell phone search and GPS tracking on vehicle violated the Fourth Amendment to right of privacy. In United States v. Jones, the police had conducted a search when they surreptitiously attached a GPS tracker to a suspect’s vehicle, triggering Fourth Amendment protections against illegal searches. In 2014, again, the court ruled that authorities generally needed a warrant to search the contents of a cellphone found in a suspect’s pocket.

Source: VOA News

What this means for users

With this decision, this means that in order for the government to receive any cell-location information about a user, the government has to provide an authorized warrant. This movement towards privacy on data sharing has privacy advocates cheering after long-awaiting a response from the high courts on the case of digital privacy.

Now, investigators and law enforcement will have to “up their game” and have to develop enough external evidence in order to meet the 51% probable cause standard for a search warrant.

Also, some of the world’s largest tech companies like Verizon Communications Inc. and AT&T, who receive over 100,000 requests annually for cell-site information, will have to shut down a majority of those requests now and begin to address new questions that come up, like access to real-time cell-site information or the longstanding debate of “privacy vs. security.”

In short, the Supreme Court has decided that the Fourth Amendment also now protects information about our location which is radiated by our devices to cell towers 24/7: a decision that defined a distinction we needed to have defined.

Signe Wilkinson by Signe Wilkinson

Still curious?

https://cdt.org/press/get-warrant-location-privacy-wins-at-supreme-court/

https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/supreme-court-scorecard-the-spring-2018-edition

http://www.scotusblog.com/2017/11/argument-analysis-drawing-line-privacy-cellphone-records/

https://www.wired.com/story/carpenter-v-united-states-supreme-court-digital-privacy/

Thank you for learning!

Thank you for joining me today to explore this recent change to our digital privacy and the Constitution’s protections of it. As always, stay safe and spread security on the internet. Until next time!

Sincerely ,

Detective Safety